Why The Study of Neurology is a Toddler: Little Neuro

While the field of neurology has grown out of its infancy, neurology is still but a toddler. We know precious little about the brain especially compared to the information explosion that has occurred in the past few hundred years leading to monumental discoveries in just about every other scientific field. We are not just the only self-aware species on earth, but we are also the only species that possesses the ability to understand language (not just communication), art, metaphor, our existence within the universe, creativity, and even religious sensibilities. (HumanUniqueness.org) Additionally, we are the only species on the planet that is able to ponder and examine how it’s own brain works. This may be why so little is known about the human brain: parts of the human brain are completely unique to humans, and therefore, animal testing is very limited in how much it can tell us about our own brain.

My interest in neurology was sparked months after my own brain injury. This interest was driven by a perceived necessity for my survival and need for recovery. Soon after my brain injury, I was discharged from the neurology department and my family and I were told by the hospital staff that “there is nothing they can do.” This lack of help that I had received from the conventional neurology department at the hospital scared me and my mother because it was our collision with the hard reality that so little is known about the human brain, and I had seriously injured mine. We didn’t know where to turn or who to turn to. I didn’t know how, or if, I was going to get better enough to lead a “normal” life.

V. S. Ramachandran is a world acclaimed neuroscientist who contributed much of the irrefutable evidence towards the idea of brain plasticity (The brain’s ability to change itself) which was a huge paradigm shift in the understanding of the brain. He describes the era before this important paradigm shift as the “bronze age of neurology”. This age understands the brain as an organ that reaches its full development by adulthood. This inaccurate perception of the brain as a static organ, therefore, assumes that if damaged or degenerated, there is little to nothing that can be done. [V. S. Ramachandran. (2011) “The Tell-Tale Brain.”]

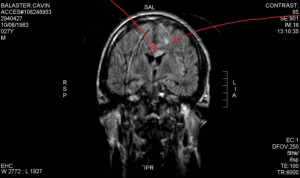

Conventional neurologists of just ten years ago and even many of those who practice today are still in the “bronze age of neurology.” (Annual Review of Neuroscience 2005) Thus, they are really very good at diagnosis, but not very robust in treatments. If I anonymously showed my MRIs to a room full of conventional neurologists (which I would love to do sometime), they could all tell me exactly what was damaged. They may all notice the Diffuse Axonal Injury that was inflicted upon my brain and the lesions of axonal brain damage within the corpus callosum; they may notice the damage to my cerebellum as well; they could possibly describe my probable impairments.

What would happen if this group of neurologists were posed the question: how can we heal this patient? If the neurologists that I asked were in the “bronze age of neurology”, they would offer no methods of recovery but maybe some pharmaceuticals to cope or find some minimal relief from the symptoms of my brain injury, as well as lifestyle adjustments to adapt to the impairment rather than minimize or eliminate it. (Researchers Gain New Insight on Traumatic Brain Injury, but Treatment Remains Elusive) If my injury was caused by a tumor or something where surgery may be beneficial, they could offer removal of parts of my brain as well, but little to nothing other than those methods. This “bad news” position that neurologists often still hold may have played a large part in ranking neurologists lower than almost all physicians on a happiness scale in July 2012. Meaning that only one year ago, neurologists reported themselves as being one of the most unhappy groups of professionals in all of the practice of medicine. (Are Neurologists Happy?)

This idea of a static brain, that prevailed in schools until the late 80s or early 90s, seems absolutely preposterous to me. [V. S. Ramachandran. (2011) “The Tell-Tale Brain.”] How can it even be suggested that the brain is fixed? Can no new skills be obtained after a human is full grown? Can an adult not still learn? Or perhaps the prevailing understanding was that learning does not rewire the brain despite the fact that in the 18th century, Michele Vicenzo Malacarne trained one group of birds to do tricks and not another group (control group), killed them all, and dissected their brains. He found that the trained birds had more extensive folding patterns in certain parts of their brains than their untrained counterparts. [Rosenzweig, Mark R. (1996). “Aspects of the search for neural mechanisms of memory”] Additionally, Eric Kandel and his team won the Nobel Peace Prize in the year 2000 “for their discoveries concerning signal transduction in the nervous system”, finding evidence that neurons constantly change. (Nobel Peace Prize 2000)

This long held belief of the brain as a static organ was indeed the “bronze age of neurology” and this belief still is abundant today within the field. It seems obvious that if an old dog can be taught new tricks, which clearly can happen, then the brain can begin to rewire itself at any age. It is even more surprising to me that this belief prevailed until relatively recently, while science, anatomy, biology, physics, electricity, and technology’s development has advanced at a rate that is unprecedented. It is paradoxical that the concepts involved in all of these fields that have advanced so drastically were developed by the very organ that was, and is, so far from being understood.

The point is that after a brain injury it is difficult to find someone who can help the survivor get better. No one prepares for a brain injury. No one expects one, nor is anyone ready if they suffer one. After I suffered a Diffuse Axonal Injury and after my own extensive research about brain injury, I realized that I have had three brain injuries in my life. Two concussions, and the Diffuse Axonal Injury.

The first one happened while skiing in Colorado when I was about ten years old. I had been skiing since i was even younger, and loved it! What’s not to love? I only remember waking up in a ski patrol cabin. My brother began telling me what happened. Apparently my brother and I were skiing when I lost control and ran into a tree. At this point in the story, a short, distorted memory took over my thoughts. it was a short and discombobulated memory of little Cavin sitting up by the tree and screaming bloody murder. I screamed until I passed out. Evidently, ski patrol came to my aid, and I was taken down the mountain to the medical cabin where I was looked after until I woke. A few hours later, I woke to my dad, my brother, and a complete stranger in a completely unfamiliar place. I had no recollection of the past few hours until my brother started to tell me what had happened and I would get vivid yet distorted memories. The memories were clear of an unclear moment in time.

The second brain injury occurred in Brooklyn, NY, one early Sunday morning. I had worked as a bartender the previous night and still had not slept when I was only a block from my house. I emerged from the subway and noticed that I had a voicemail, so I proceeded to check the message. One minute I’m checking my messages, and the next moment, I find myself on the sidewalk with a terrible headache. While I was never unconscious, I had been punched in the face which sent my head into the brick wall that I was walking next to before falling to the ground. This was my first encounter with a mugger, after 5 years of living in Bushwick, Brooklyn. The attacker ended up wanting my phone (a cheap Samsung flip phone), which I dropped on the ground for him and he ended up taking nothing from me, while I walked away with a brain injury that left me with vertigo (dizziness) for a few weeks. Vertigo is perhaps the most common symptom after a brain injury. (VestibularDisorder.com)

Many of us have had brain injuries and are functioning. My last injury was especially severe, but many people function with less severe brain injuries all over who are unaware of the fact that they have had a brain injury. I read a statistic that said “a person with two TBIs is eight times more likely to have another than is a person who has never had head trauma.” (Traumatic Brain Injury: Effects of Closed Head Injury) This statistic is based on epidemiological data, meaning that we can only draw a correlation. One brain injury may imply that the brain is easier to be re injured (as my mom thought it may mean), but it could also mean one’s lifestyle and circumstances may make them more likely to suffer another brain injury. I lean towards the latter because it is similar to the idea that drivers that drink two or more alcoholic drinks a day are more likely to have a car accident. While there are drivers that won’t, there is a correlation that I would assume is attributed to lifestyle. Similarly, if a football player has two brain injuries, he is still a football player, and football is a contact sport that may result in a brain injury. In my own studies of the brain, I have yet to see an explanation of why the former may be true.

Neurology is making progress, and I’d like to contribute to that progress. I am very excited to be starting a TBI recovery program in the next few months, and I look forward to working with other brain injury survivors and learning as much as I can about this three pound gelatinous mass that is housed within the skull. This toddler, that is neurology, will grow up and we will understand more as time passes. It is an exciting time for neurology and I look forward to my involvement in this field in the future.

Comments

Very interesting! I have a pineal cyst/ tumor and I’m very interested in how our brains can possibly heal itself. I haven’t had surgery as of yet. Praying that God blesses you with great knowledge as you continue on your journey for healing. Hopefully it will help people like myself be able to get the help we need in order to deal with our new selves.

Hi Sandra!

Thank you so much. Neuroplasticity is amazing, and I very much hope to see our understanding of the brain flourish in the next decade! For now, I’m working on creating a resource of quality resources of practitioners who understand the nervous system in a big way. Stay tuned. 🙂